Today it’s all about floats. How a float (number) is represented in binary, and in machine? Let’s try an example in Python. I found this topic to be really interesting as we’re going to the very basics of computing!

I pick the number 263.3 for demonstration because I found this amazing video explaining the same topic on a piece of paper (and in single-precision), and for simplicity and reference, I decide to use the same number.

Floating Representation

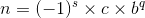

First, according to the IEEE 754 standard, a floating-point number can be basically represented by the equation:

In a human-readable form, just like a scientific notation, a number can be represent as:

1

263.3 = (-1)**0 * 2.633 * 10**2

Where s is 0, c is 2.633, b is 10, and q is 2. We will basically represent a floating-point number this way.

In binary, 263.3 can be represent as:

1

(-1)**0 * 1.0000011101001100110011001100110011001100110011001100 * 2**8

Where s is 0, c is 1.0000011101001100110011001100110011001100110011001100, b is 2, and q is 8. You can refer to the video link above for a detailed walk through.

The mantissa part consists of 52 digits, which is standard for double-precision (64-bit) floating-point number. The full 64-bit binary of this number is:

1

0100000001110000011101001100110011001100110011001100110011001101

This number consists of 3 parts: sign (1 bit), exponent (11 bits), and fraction (52 bits). For a positive number, sign is 0; exponent in decimal is 8 + 1023 (bias) = 1031, and fraction is what’s after the dot:

1

0 10000000111 0000011101001100110011001100110011001100110011001101

Diving the bits by every 4 bits:

1

0100 0000 0111 0000 0111 0100 1100 1100 1100 1100 1100 1100 1100 1100 1100 1101

How To Do It in Python

We can get hex value (basically scientific notation in hex) of a floating-point number with the float.hex() function:

1

2

>>> float.hex(263.3)

'0x1.074cccccccccdp+8'

Which can be interpreted as:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

S = 1

M = 1 + 0/16 + 7/16**2 + 4/16**3 + 12/16**4 + 12/16**5\

+ 12/16**6 + 12/16**7 + 12/16**8 + 12/16**9 + 12/16**10\

+ 12/16**11 + 12/16**12 + 13/16**13

E = 2**8

n = S*M*E

>>> (S, M, E, n)

(1, 1.028515625, 256, 263.3)

If you want to check the actual binary representation of the number, you can use the built-in struct module to pack the number to C struct:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

import struct

n_be = struct.pack('>d', n) # big endian

n_le = struct.pack('<d', n) # little endian

>>> n_be

b'@pt\xcc\xcc\xcc\xcc\xcd'

>>> n_le

b'\xcd\xcc\xcc\xcc\xcctp@'

n_be_bin = ''.join([format(x, '08b') for x in n_be])

n_le_bin = ''.join([format(x, '08b') for x in n_le])

>>> n_be_bin

0100000001110000011101001100110011001100110011001100110011001101

>>> n_le_bin

1100110111001100110011001100110011001100011101000111000001000000

And you get the same 64 bits from n_be_bin! It’s worth noting that for this exercise we should examine the big endian binary representation instead of little endian that most platforms use. To learn more about big endian and little endian, checkout this wiki page.

Thank you for reading!